Modern venture capital traces its roots to the post-WWII era. In 1946, American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC) was founded by Georges Doriot as one of the first venture firms. ARDC was a publicly traded vehicle that raised capital from outside the traditional wealthy-family circles (including institutional money) – a revolutionary idea at the time. ARDC’s landmark success came with its 1957 investment of $70,000 in Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) (for 70 % ownership) plus a $2 million loan, which turned into many times that value after DEC’s IPO in 1966. This demonstrated the venture model’s potential: high-risk equity investment in technology startups could yield outsized returns.

Yet, ARDC was not a “fund” in today’s sense; it operated more as an evergreen investment company and even took majority stakes (e.g., 77 % of DEC). The true structural template for VC funds emerged in 1958–59, when ARDC alumni and others set up the first limited partnerships. Notably, Draper, Gaither & Anderson (DGA) formed a $6 million fund in 1959 – structured as a 10-year limited partnership with a 2.5 % annual management fee and 20 % carried interest for the GPs. This “2 & 20” model with a decade lifespan became the blueprint for virtually all VC funds thereafter. The alignment of incentives was clear: GPs (general partners) only profit significantly if investments succeed (via carry), aligning them with LPs (limited partners). DGA’s success inspired others: in 1961 Arthur Rock co-founded Davis & Rock, another 2 & 20 fund that, among other deals, invested in Fairchild Semiconductor and later Intel. Greylock Partners followed in 1965, founded by ARDC veterans and likewise adopting the limited-partnership format. By the late 1960s, the basic economics (management fee, carry, fixed-life fund) and governance norms of venture investing were in place.

Early Silicon Valley received critical DNA from these proto-VC efforts. For example, when Arthur Rock helped eight defectors from Shockley Labs (the “Traitorous Eight”) form Fairchild Semiconductor in 1957, a key condition was equity ownership for the technical founders – a sharp break from the norm of large corporations. This ethos of giving founders and early employees substantial stock (and later, stock options) became a governance norm transferred to Silicon Valley startups. It aligned talent with investors, mirroring the GP/LP alignment at the fund level. Additionally, early venture deals established that VCs would often take board seats and actively mentor companies – a practice Doriot himself espoused, as he taught entrepreneurship at Harvard. Reinvestment (“recycling”) of gains was also present: ARDC, as a public VC, could reinvest its profits continuously, whereas the new LP funds wrote provisions to reinvest early returns into new deals within the fund’s life. These practices – active governance, equity incentives, and long-term commitment of capital – formed the cultural and structural bedrock for venture capital. All these would prove prescient for the crypto era, which would grapple with aligning decentralized project teams with investors in new ways.

Institutionalization (1968–1999): From Niche to Mainstream

By the late 1960s, venture capital was still a relatively small, clubby industry, but it was about to scale massively. Key policy shifts in the 1970s unlocked institutional money, transforming VC into a mainstream asset class. A pivotal change came with the 1978 US Revenue Act, which slashed the capital-gains tax rate from 49.5 % to 28 %, dramatically increasing the after-tax returns from successful venture investments. Almost immediately, capital flowed in: new commitments to VC funds jumped from a mere $68 million in 1977 to nearly $1 billion in 1978. Then in 1979, the Department of Labor clarified the ERISA “prudent-man” rule, explicitly allowing pension funds to invest in venture capital. This was a game-changer – vast pools of capital that had been off-limits (pensions, insurance) could now seek the higher returns of VC. By 1983, annual new commitments to venture funds exceeded $5 billion, up more than 50 × from the mid-1970s. In short, policy catalyzed the VC boom: the twin boosts of a friendly tax regime and pension-fund participation gave the industry a long-term capital base it never had before. (For context, many of the LPs now allocating to crypto funds – endowments, family offices, etc. – first entered venture in this era of newfound legitimacy and attractive returns.)

The 1980s and 1990s saw venture capital mature alongside the computer and internet industries. The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 further spurred innovation (and indirectly VC deal flow) by allowing universities and small businesses to own and license patents from federally funded research, leading to a wave of spin-out startups from academia (particularly in biotech and computer science). Venture firms eagerly backed these tech-transfer companies, bridging lab innovations to market – a precedent for how crypto VC would later fund open-source protocol developers spinning out of research labs and hacker communities.

Throughout the ’80s, VC grew steadily, then exuberantly in the ’90s. The IPO boom of the early 1980s (e.g., Genentech in biotech, Apple in personal computing) provided successful exits that proved the VC model at scale. In 1980 alone, 88 VC-backed companies went public. The subsequent stock-market crash of 1987 caused a brief dip, but by the 1990s, the dot-com wave was underway. Venture investment exploded in the latter half of the ’90s, peaking in 1999 – the year of Pets.com and Webvan – when U.S. VC investment across all sectors hit an unprecedented ~$105 billion (in 2021 dollars). Venture capital had gone from a cottage industry to a driving force of the economy, and Silicon Valley became synonymous with high-growth startups. Crucially, the venture-partnership structure proved resilient: even as fund sizes grew (from tens of millions in the ’60s to hundreds of millions by the ’90s), the 2 % / 20 % fee-carry model and ~10-year life remained standard, aligning big rewards for GPs with big outcomes for companies. Funds launched in this era (Sequoia, Kleiner Perkins, Accel, NEA, etc.) institutionalized investment committees, rigorous due-diligence processes, and portfolio-management techniques (like reserving capital for follow-ons) that would later be adopted by crypto funds seeking similar professionalization.

One specific structural innovation was the stock-option pool for employees. In 1980s Silicon Valley, it became standard that ~10 – 20 % of a startup’s equity be set aside as options to attract and retain talent. This practice originated from success stories like Apple and Microsoft, which minted millionaire employees and thus drew waves of skilled labor into startups. It ingrained the idea of broad-based ownership in tech companies, aligning employees with investors and founders. Later, crypto projects would emulate this through mechanisms like token allocations for core contributors – effectively, token options. The DNA of incentive alignment runs straight from the Fairchild/HP era of stock options to modern token-vesting schedules.

Governance norms also evolved: VCs in the ’80s and ’90s became deeply involved in company strategy, often taking board seats commensurate with their ownership. They emphasized milestones, professional management (sometimes even ousting founders in favor of seasoned CEOs), and staged financing (tranches released as KPIs hit). While some of these hands-on practices clash with the decentralized, founder-centric ethos of crypto, the underlying principle of active investor support and oversight carried forward. Even crypto funds today often use SAFEs/SAFTs with board-observer rights or on-chain governance participation, reflecting the idea that capital comes with guidance and accountability – a norm set in this institutional VC age.

Key Inflection Points & Lessons: The institutionalization era taught that venture capital is highly cyclical and sensitive to policy and macro shifts. The late ’90s dot-com bubble and burst underscored that soaring investment volumes can presage painful corrections – 2000 was a “high-water mark… not again replicated until 2020” for overall venture funding. When the bubble burst, many VC funds and LPs saw negative returns, leading to a pullback in the early 2000s. This memory echoed in crypto: 20 years later, the ICO boom and 2021 boom would follow a similar boom-bust-investor-exodus pattern. The lesson for long-term LPs was to commit to the asset class through cycles and be wary of hype phases – wisdom equally applicable to crypto VC allocation now. Crucially, the regulatory and structural innovations (prudent-man rule, capital-gains tax rates, university tech-transfer policies) set precedents for how external factors can unlock new capital for venture – analogous to how clear crypto regulation or new financial instruments (ETFs, etc.) could unlock fresh capital for crypto markets. In essence, by 1999 the venture industry’s genealogy had branches around the world, robust best practices, and a track record that would soon inspire the first funds dedicated to an emerging technology called cryptocurrency.

Dot-Com to Mobile (2000–2009)

The turn of the millennium brought the dot-com crash, a major inflection point. After 2000, venture capital sharply contracted as the NASDAQ collapse and startup failures triggered a funding drought from 2001–2003. VC investment plunged ~80% from 2000 to 2002, and many late-90s funds delivered poor returns. This painful reset parallels crypto’s 2018 "crypto winter" and 2022 downturn—markets that surge can crash, with rewards often coming in the next cycle. Indeed, venture capital recovered gradually in the mid-2000s, driven by Web 2.0 (social media, SaaS) and later the mobile revolution (smartphones, apps). By 2007–2008, companies like Facebook and YouTube emerged, and Apple's 2007 iPhone unlocked a new app economy. However, total VC funding didn’t surpass the 2000 peak again until 2020, underscoring the need for patience—a cautionary note for crypto investors after the 2021 highs and subsequent 2022–2023 slump.

A key 2000s shift was startups staying private longer. While IPOs typically occurred within 4–5 years in the 1990s, by the late 2000s, companies like Facebook took around 8 years (2004–2012), and Uber even longer. This was partly due to abundant late-stage capital and regulatory burdens like the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Longer liquidity paths prompted the emergence of secondary markets for private equity around 2007–2009, with platforms like SecondMarket (founded by Barry Silbert) and SharesPost facilitating trading in pre-IPO shares of companies such as Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter, especially after the 2008 crisis stalled IPOs.

SecondMarket initially traded illiquid assets but found its niche in private tech stocks by 2009, notably Facebook shares. By 2010–2011, SecondMarket and SharesPost regularly enabled secondary trading, foreshadowing crypto token liquidity dynamics. These platforms demonstrated appetite for liquidity before traditional exits and provided price discovery for private assets-proto-exchanges for venture assets, akin to modern crypto exchanges.

Significantly, secondary markets broadened investor participation (hedge funds, pre-IPO funds, wealthy individuals) into late-stage companies, analogous to ICOs and token offerings enabling broader, faster global investment in early-stage tech projects. ICOs can be seen as extending this secondary-market trend, offering direct, immediate liquidity by issuing tokens instead of shares.

Governance impact: Secondary markets introduced friction, prompting firms like Facebook to impose transfer restrictions. This mirrors crypto debates on token float control. Regulators also intervened, with SEC rules (500-shareholder-rule modifications, Reg A+ and CF expansions) modernizing private-share trading, paralleling today’s regulatory efforts for token markets.

The wider 2000s venture scene saw other innovations and challenges. Post-dot-com bust scrutiny questioned the traditional VC model, prompting experiments with corporate venture arms and venture debt. Global VC expanded rapidly, particularly in Europe and Asia, supported by government initiatives, ending Silicon Valley’s monopoly. Crypto’s inherently global nature amplified this trend, with early global developer communities and ICO activity. By 2010, venture capital had a playbook for global scale that crypto funds later adopted.

Takeaway: The 2000s taught VC vital lessons in liquidity management and adaptability, prefiguring crypto’s innovations. Secondary markets anticipated token vesting and early liquidity-both serving investors seeking quicker exits than traditional timelines. The decade’s innovations (secondary exchanges, private-stock trading frameworks) laid foundations turbo-charged by crypto’s 24/7 global trading. Limited partners examining the 2000s recognize cyclical patterns and early-liquidity mechanisms essential for assessing crypto VC today.

Bitcoin-Only Era (2009–2012): A Curiosity Outside VC’s Gaze

The launch of Bitcoin in January 2009 – amid the Great Recession – introduced a radically new concept: a decentralized, digital form of money and store of value, powered by blockchain technology. Yet in these formative years, institutional venture capital paid scant attention. Bitcoin’s emergence was driven by cypherpunks, cryptographers, and hobbyists on forums, not the halls of Sand Hill Road. Funding for Bitcoin-related endeavors came mostly from personal passion (early miners reinvesting their coins) and a few angel investors who were true believers. For example, Roger Ver (often called “Bitcoin Jesus”) funded several Bitcoin startups early on, and Jed McCaleb created and sold the Mt. Gox exchange largely self-funded. But the traditional VC firms largely sat on the sidelines. In fact, in all of 2012, Bitcoin startups raised only about $2 million in venture capital combined – essentially a rounding error in global VC statistics. By comparison, that same year saw overall VC investment around $50 billion globally. Bitcoin was invisible in portfolios.

Why did mainstream VCs initially ignore Bitcoin? Several factors were significant:

Perceived Illegitimacy and Risk: From 2009–2011, Bitcoin was little-known beyond niche tech circles and frequently linked to illicit activities (e.g., Silk Road). Its ambiguous legal status and decentralized, non-equity structure left traditional investors without a framework for investing. The concept of purchasing tokens or currencies was foreign, and no significant tokens aside from BTC existed until 2012. Prominent VCs like Fred Wilson of Union Square Ventures famously passed on early Bitcoin opportunities, only embracing them later as clearer startup models emerged around 2013 with exchanges and wallets-a hesitation reminiscent of early computing investors awaiting a concrete business case.

Lack of Startups/Teams: Before 2013, very few investable Bitcoin-related companies existed. Bitcoin itself had no formal organization, and its initial ecosystem (exchanges, payment processors, mining) relied on informal initiatives. Only by 2011–2012 did startups like BitPay and Coinbase emerge, creating investable vehicles. Prior to that, VCs had no suitable investment targets, as direct BTC purchases raised custody and compliance concerns and conflicted with the traditional venture model.

Scale and Exit Concerns: Bitcoin’s market cap remained under $1 billion until 2013, appearing small and slow-growing to VCs aiming for multi-billion-dollar exits. Without clear IPO or M&A pathways, monetizing Bitcoin investments appeared uncertain. Many investors later admitted overlooking the potential business model and value capture, missing early recognition of Bitcoin as a new asset class.

Despite mainstream hesitation, specialized investors emerged. In 2012, Barry Silbert founded Bitcoin Opportunity Corp., an early angel fund for Bitcoin startups (later becoming Digital Currency Group). Additionally, Adam Draper’s Silicon Valley incubator Boost VC launched a Bitcoin-focused accelerator in 2013, providing crucial early support. These entities operated at the fringes until Bitcoin’s price surge to $1,000 in 2013 finally drew mainstream VC attention.

Historical parallel: The situation resembled the pre-venture era of early tech - like how in the 1930s and early ’40s, innovative projects were funded by government grants or hobbyists because formal venture capital didn’t exist until after WWII. Bitcoin in 2009–2012 was nurtured by its community and a libertarian/open-source ethos rather than VC money, highlighting that transformational innovations can gestate outside conventional funding channels. For LPs and observers, this era is a reminder that first movers are not always VCs themselves; sometimes the opportunity needs to ripen. By 2013, as we’ll see, that ripening occurred and the First Crypto VC Wave began – marking the true start of venture capital genealogy branching into blockchain.

First Crypto-VC Wave (2013–2016)

2013 was a breakout year for crypto venture. Bitcoin’s price surged (from ~$13 in Jan to over $1,000 by Dec), grabbing headlines and forcing tech investors to pay attention. More importantly, real startups formed around Bitcoin and other nascent cryptocurrencies, providing investable equity for VCs. The result: venture capital investment in crypto jumped dramatically. In 2013, blockchain/Bitcoin startups raised on the order of $90 million in VC – up from virtually $0 the year before. It was still tiny by VC standards, but the trajectory had changed.

Several must-cover nodes in this first crypto-VC wave illustrate how classical VCs adapted to this new domain:

Coinbase: In summer 2013, Coinbase (founded by Brian Armstrong and Fred Ehrsam in 2012) raised a $5 million Series A led by Union Square Ventures (USV), with participation from Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) and others. This deal was hugely symbolic: USV’s Fred Wilson was a prominent Web 2.0 investor (Twitter, Tumblr, etc.), and a16z was the era’s preeminent VC firm. Their stamp of approval signaled that crypto had arrived as a legitimate startup sector. The investment was a traditional equity round – buying shares of Coinbase, a Delaware C-corp exchange business – showing VCs applying their usual model (own part of a company) rather than buying tokens. That was logical, as Coinbase had no native token (and still hasn’t to this day), and the regulatory environment for tokens was unformed. Notably, the terms were standard: preferred stock with rights typical of any Silicon Valley deal. However, one adaptation for crypto risk was heightened compliance clauses – investors needed Coinbase to actively manage regulatory risk (e.g., KYC/AML processes) to protect the company’s legitimacy. The success of the Coinbase deal (valued ~$70 million then; IPO’d in 2021 at >$80 billion) validated to the VC community that one could achieve venture-scale returns in crypto via equity in picks-and-shovels companies (exchanges, wallets).

Ripple (OpenCoin): Also in 2013, Andreessen Horowitz made its first crypto investment by joining a $2.5 million round in OpenCoin, the startup developing the Ripple protocol for bank payments. Google Ventures and Lightspeed also invested. Ripple was unique in that it did have a native token (XRP), but the investment was in the company’s equity. This raised an interesting question: how to value a company whose product is an open-source protocol with its own currency? VCs essentially bet that the company could create enterprise software or services around the Ripple network (and perhaps hold a lot of XRP that might appreciate). Here we see early recognition that a hybrid value model could exist – part equity value, part token value – though at this stage tokens were mostly viewed as digital commodities, and VCs didn’t explicitly get XRP in the deal (aside from any the company treasury held). It highlighted a need for term sheet adaptation: down the road, if the protocol succeeded and XRP’s value soared, would equity holders fully benefit? Such concerns led some term sheets to include provisions like “Most Favored Nation” clauses for token issuance – ensuring early investors could opt in if a token offering happened later. In 2013–2014, these were nascent ideas; most deals still presumed value came via equity exits.

Birth of Crypto-Focused Funds: The period saw the inception of dedicated crypto venture funds, often by industry insiders. Blockchain Capital (originally Crypto Currency Partners) was founded in 2013 by Bart Stephens, Bradford Stephens, and Brock Pierce specifically to invest in Bitcoin and blockchain startups. They raised a modest ~$10 million fund – effectively creating one of the first crypto-native VC firms. Similarly, in 2013, Dan Morehead (a former Tiger Management macro investor) launched the Pantera Bitcoin Fund, initially structured more like a hedge fund to hold Bitcoin and invest in startups. Pantera would later spawn venture funds as well. These specialized funds brought deep crypto expertise and were willing to tackle crypto-specific issues (like custody of digital assets, understanding protocol tech) that generalist VCs were still grappling with. They also often negotiated innovative deal structures out of necessity – for instance, Pantera sometimes bought equity with warrants for tokens if a startup was planning a blockchain launch. This was the beginning of “equity plus token rights” deals that would become common by 2016–2017. Traditional term sheets didn’t have language for token allocations, so lawyers began drafting new terms.

Other Notable First-Wave Investments: 2014 saw Benchmark invest in Bitstamp (a major European crypto exchange). IDG Capital (a big Chinese VC) invested in Coinbase’s Series B in 2014, indicating global interest. Andreessen Horowitz and Union Square together backed Mediachain in 2016 (a decentralized media attribution protocol), one of the earlier non-currency blockchain startups. By 2015–2016, the venture landscape included projects like Ethereum – though Ethereum famously raised capital via a crowdsale of Ether in 2014 (raising 31,000 BTC ≈ $18 million), largely without VC money at the start. Some VCs, like Boost VC and Frontier Ventures, did buy small amounts of ETH pre-launch, but for the first time VCs were not the primary capital source – the community was. This was a harbinger of the ICO era, but at the time it was an outlier.

By 2016, the concept of “SAFEs with token warrants” or convertible notes that might convert into tokens was emerging in legal circles, anticipating the ICO wave. Traditional VC agreements began sprinkling in clauses about tokens. For example, an investment in a protocol startup might say: if the company ever issues a utility token, investors either get a certain allotment or the option to acquire tokens at a discount. This was a direct adaptation to crypto risk – namely, the risk that value would shift from equity to a token not originally contemplated. These contract tweaks were still evolving and not widely standardized until the SAFT in late 2017, but their roots lie in these 2013–2016 deals as pioneers felt out the new territory.

ICO Boom (2017–2018):

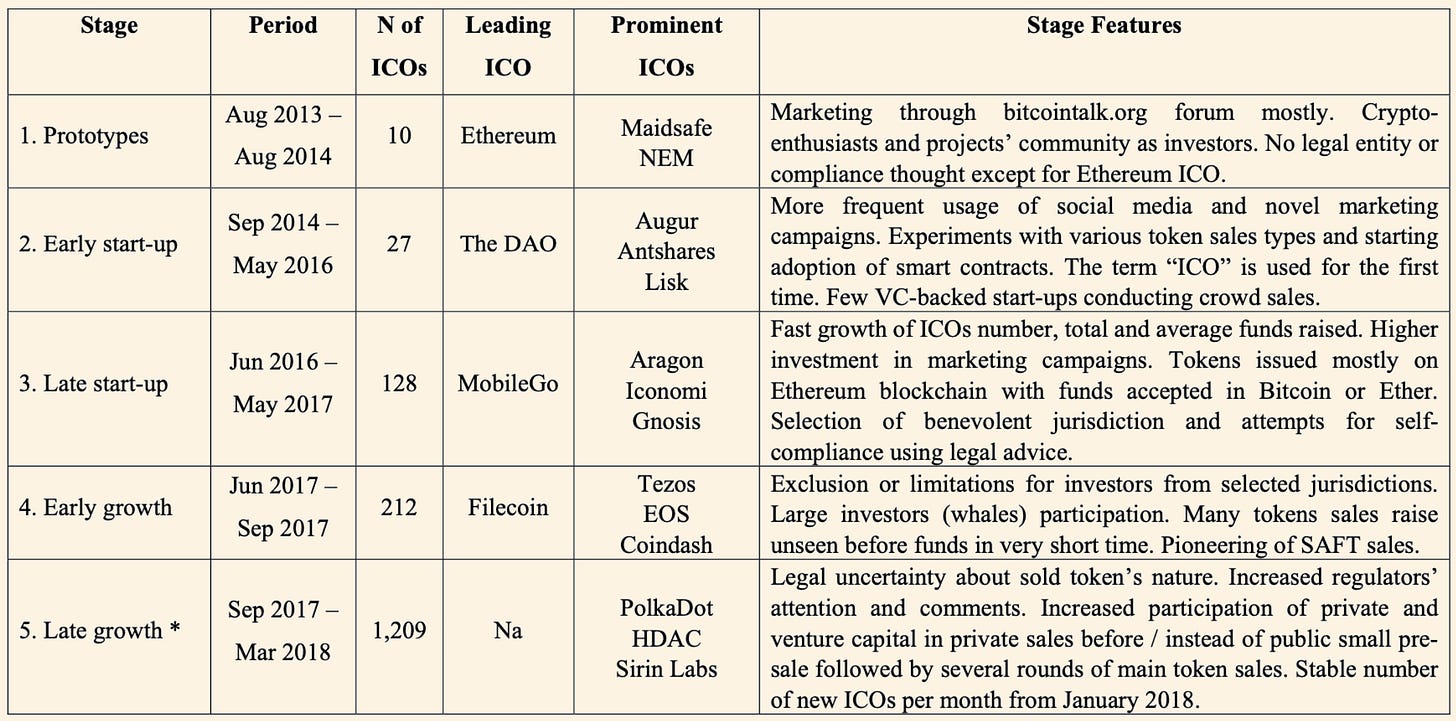

In 2017, crypto funding underwent a paradigm shift with the explosion of Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs). What had been a VC-driven niche industry transformed as startups discovered they could raise millions from a global crowd by issuing tokens, often with only a whitepaper. The scale was unprecedented and marked a major inflection point in venture genealogy – akin to an evolutionary branch splitting off.

The numbers tell the story. In 2017, nearly 800 ICOs collectively raised about $5 billion, an impressive figure given that blockchain startups raised only ~$1 billion via traditional VC—a 5× higher capital flow through token sales. This trend intensified in 2018, with ICO fundraising reaching $7.8 billion, even amid a crypto downturn. By contrast, total venture investment into blockchain companies was roughly $4 billion. Entrepreneurs recognized they could bypass traditional gatekeepers (VCs) to access crypto-enthusiast capital directly.

Structurally, tokens rewired the classic VC J-curve. Traditionally, VC funds deploy capital over ~3 years and await exits ~5–7 years later, resulting in initial negative returns that later turn positive—the J-curve. ICO-era funds saw portfolio liquidity within months, not years. For instance, a fund buying tokens at pre-sale often sold on exchanges shortly after launch (3–6 months). During 2017’s bull market, tokens frequently appreciated rapidly, allowing NAV spikes and early LP distributions, flattening the J-curve. Conversely, liquid tokens could quickly lose value during downturns, unlike relatively stable illiquid equity. Essentially, rapid liquidity and volatility replaced steady value growth. Some crypto funds actively managed profits, resembling hedge funds, while others adhered to venture-style holding strategies, sometimes adversely affected in 2018’s bear market.

The ICO surge introduced new fund structures, notably crypto-native hedge funds (open-ended, quarterly liquidity) rather than traditional 10-year closed funds. Examples include Polychain Capital, founded by Olaf Carlson-Wee in 2016 with VC backing and hedge fund fee structures (2% management, 30% performance). MetaStable Capital, co-founded by Naval Ravikant, was similar. They bypassed lengthy diligence, evaluating code, token economics, and community traction, using SAFTs, SAFEs, and simple token purchase agreements instead of traditional term sheets. Their approach merged venture thesis with hedge fund tactics, departing significantly from classic fund structures. Traditional LPs faced challenges adapting to this model, yet attractive early returns (often 10×+ annually) encouraged adoption, foreshadowing today's blended VC and hedge fund LP bases.

SAFT and legal engineering: Late 2017 saw securities law concerns addressed by introducing the SAFT (Simple Agreement for Future Tokens), inspired by Y Combinator’s SAFE equity notes. SAFTs allowed accredited investor participation in private pre-sales, complying with U.S. securities regulations by initially treating these contracts as securities. Filecoin’s 2017 ICO using a SAFT raised ~$257 million, becoming standard practice for token sales in 2017–2018. For VCs, SAFTs provided familiar private-funding structures, although legal clarity remains debated, especially after the SEC’s 2019 actions against issuers like Telegram. Nevertheless, SAFT bridged venture funding with the token paradigm, akin to Series A financing but with much earlier liquidity.

Rewriting the rules: The ICO era reshaped venture norms:

Due Diligence and Speed: Traditional VC diligence took months, whereas ICO deals closed rapidly, often within days or hours, using code and whitepapers as primary diligence tools. Funds developed smart-contract auditing capabilities and assessed decentralized community traction, hiring technical experts and taking greater risks, sometimes resulting in fraud or weak projects.

Global and Retail Participation: ICOs involved thousands of global retail buyers, diminishing the exclusivity of venture capital. Funds had to emphasize added value beyond capital—marketing, exchange listing assistance, developer recruitment, and governance guidance—to justify their relevance.

Token Economics & Vesting: Token investments required understanding new dilution mechanics, vesting schedules, and comprehensive "tokenomics" (token supply, inflation, and distribution). Investors often negotiated lock-up periods (6-month to 1-year) to manage immediate liquidity risks, mirroring IPO lock-ups and M&A earn-outs, applying traditional financial wisdom to token deals.

The DAO and security concerns: The 2016 DAO incident on Ethereum, raising ~$150 million before a catastrophic hack, led to a hard fork and regulatory scrutiny. The SEC’s subsequent DAO Report declared DAO tokens securities, prompting projects toward SAFTs and private sales. The event underscored the importance of smart-contract security and governance, making code audits and community involvement essential for crypto VCs.

By late 2018, the ICO bubble burst; Ethereum prices fell sharply, and many ICO startups failed. Equity-based crypto funding rebounded in response, emphasizing traditional VC strengths—due diligence, governance, and long-term support—as key to surviving downturns. ICOs tested but did not replace venture capital, underscoring the continued value of professional investment support.

Post-ICO Winter (2019–2020)

After the frenzy of 2017–2018, the crypto sector entered a retrenchment known as “crypto winter.” As token prices languished through 2019, many hyped projects disappeared, and regulatory scrutiny (especially by the U.S. SEC) intensified. Venture capital in crypto didn’t vanish – it refocused on quality over quantity. Total blockchain-related VC funding in 2019 remained relatively robust (around $2.7 billion across 600+ deals globally), indicating continued serious investor interest, albeit at saner valuations, often returning to equity.

This period saw the rise of crypto-native VC firms and established firms with dedicated crypto efforts, fostering hybrid funding models:

Emergence of Paradigm: In 2018, amid the bear market, Paradigm was founded by Matt Huang (formerly Sequoia) and Fred Ehrsam (Coinbase co-founder) with a $400 million fund. Its launch signaled crypto VC professionalization, blending rigorous traditional VC investing with deep crypto technical expertise. Paradigm pursued hybrid investments (equity and tokens) and network governance, employing in-house researchers and engineers, echoing operational support trends from classical VCs in the 1990s. Paradigm emphasized a long-term outlook, looking 10+ years ahead, countering the quick-win mentality of the ICO era.

a16z Crypto and Big Funds: Mid-2018, Andreessen Horowitz launched “a16z crypto”, a dedicated $300 million fund. Despite market conditions, a16z doubled down, declaring crypto a transformative computing paradigm requiring patient capital. The fund registered as a financial advisor to manage tokens without regulatory conflicts, blending VC with hedge-fund-like management. Top-tier VC firms like Union Square Ventures, Polychain, and Blockchain Capital also raised significant crypto-focused funds, attracting institutional LP capital at improved valuations.

Hybrid Deal Structures: By 2019, funding rounds frequently included equity and token warrants, enabling investors to capture both network and company value. This approach aligned company management with token holders, reducing conflicts. Lawyers standardized terms, introducing agreements like Simple Agreements for Future Equity/Tokens (SAFE-T), convertible into equity or tokens at future financings or network launches.

Continued Regulatory Navigation: During 2019–2020, regulatory actions persisted. High-profile SEC cases (e.g., Telegram’s $1.7 billion and Kik’s token sales) chilled large public ICOs. Projects shifted towards private funding and geo-restricted offerings to avoid U.S. jurisdiction. Crypto VC funds increasingly advised on compliant structuring. Exchanges tightened listing standards, creating a more controlled, contract-based environment favorable for private VC deals.

Notable Investments and Themes: Despite market chill, notable investments occurred. Binance, largely self-funded, took strategic investments (e.g., Temasek in 2020), reflecting continued sovereign wealth interest. DeFi emerged prominently (MakerDAO, Compound, Uniswap), with VCs acquiring tokens directly through SAFTs. Enterprise blockchain briefly attracted VC but failed to gain traction, underscoring the value in open networks.

An interesting hybrid model emerged with Digital Currency Group (DCG) and ConsenSys, acting as venture studios rather than traditional funds. By 2020, even these players sought outside investment, reinforcing the enduring relevance of the GP/LP model.

Impact on LP perspective: By late 2020, early crypto venture funds reported substantial paper gains (a16z crypto fund surpassed 10× returns post-Coinbase IPO). However, volatility meant varied IRRs depending on timing. LPs evaluated metrics like TVPI and DPI, with some funds making in-kind token distributions, prompting LPs to establish new policies for digital asset custody and liquidation.

Metaverse/Web3 Boom (2021)

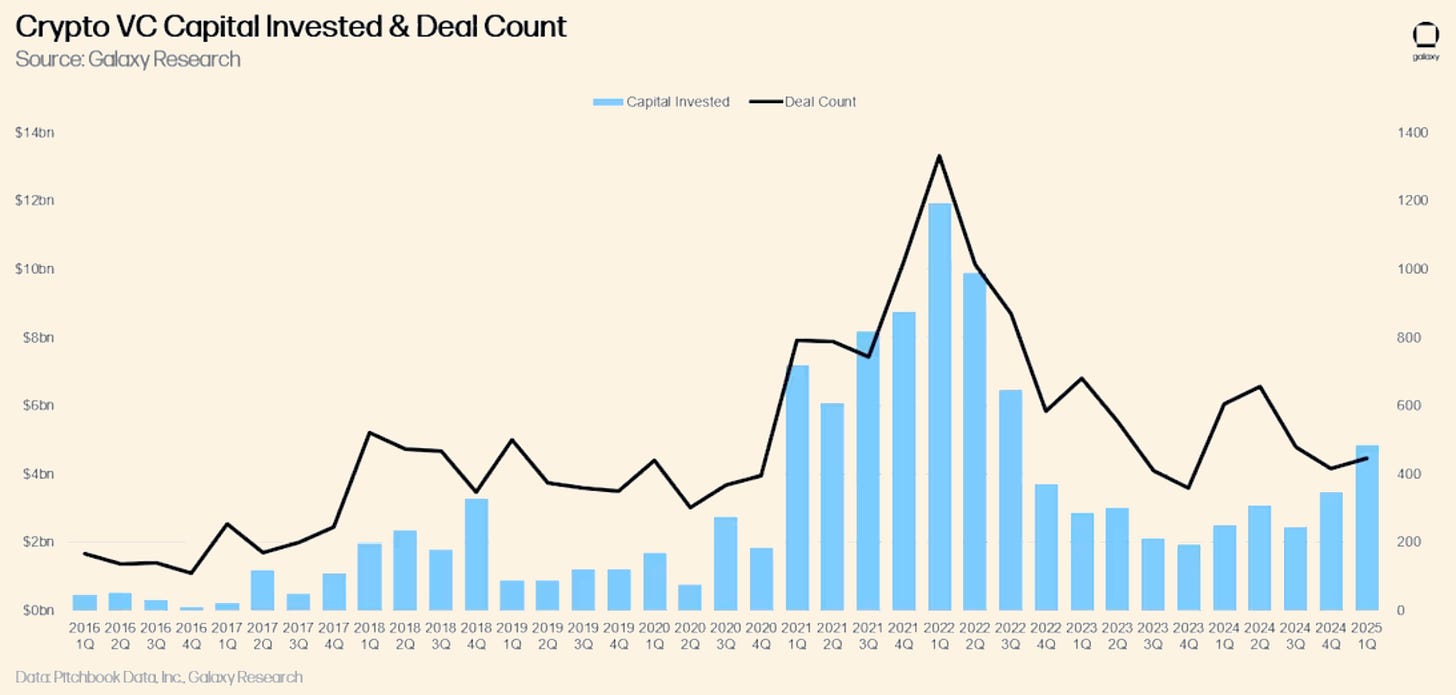

2021 was a record-breaking year for crypto venture capital, marking crypto’s mainstream arrival in investors' eyes. Venture capitalists poured approximately $33.8 billion into crypto and blockchain startups, surpassing the total of all previous years combined. Remarkably, this was nearly 5% of global venture funding, extraordinary for a formerly niche sector. Deal volume also peaked, with over 2,000 rounds—double the 2020 count. This “Web3 boom” was driven by surging crypto markets (Bitcoin hitting $69k, Ethereum $4.8k), the rise of DeFi, NFTs, and the Metaverse, and pandemic-era capital seeking high-growth returns. It attracted numerous “tourist” investors, new entrants unfamiliar with crypto, significantly altering funding dynamics.

Key features of 2021’s crypto VC boom include:

Mega-Rounds & Unicorns: Crypto startups secured unprecedented multi-billion-dollar late-stage rounds. FTX, established in 2019, raised a $900 million Series B at an $18 billion valuation in July, involving investors like Sequoia Capital, SoftBank, Tiger Global, Temasek, and BlackRock—then the largest private crypto round ever. Similar mega-rounds occurred for BlockFi (lending), Dapper Labs (NFTs), and Sorare (fantasy sports NFTs). Over 60 crypto unicorns emerged, up significantly from previous years, with median valuations soaring to $70 million, 141% higher than economy-wide VC deals.

New Entrants (“Tourist” Investors):

Crossover hedge funds (Tiger Global, Coatue, D1 Capital) aggressively funded crypto startups, pushing valuations skyward, though many retreated after 2022 losses.

Sovereign wealth and large asset managers (Temasek, GIC, Mubadala, BlackRock, Goldman Sachs) invested directly, fostering institutional compliance.

Corporate VCs and tech giants (PayPal Ventures, Visa, Microsoft’s M12, Ubisoft) invested strategically to understand blockchain’s impact on their core businesses.

Broader LP Base: Endowments, pension funds, foundations, and family offices openly backed crypto funds. Notably, a16z raised a $2.2 billion Crypto Fund III, while Paradigm closed an oversubscribed $2.5 billion fund.

Areas of Frenzy – NFTs, Metaverse, DeFi:

NFT platforms (OpenSea, Dapper Labs) saw valuations surge post-high-profile sales like Beeple’s $69 million artwork.

DeFi and Web3 protocols attracted diverse VC backing, including equity, tokens, and hybrid investments.

Infrastructure firms (wallets, analytics, custody, APIs, scaling networks) attracted funding as stable long-term bets.

Tourist Investor Behavior: Experienced crypto investors cautioned that many poorly vetted ideas received funding. By mid-2022, numerous “tourist” investors exited swiftly upon market downturn.

Why the rush? Investors were motivated by FOMO, near-zero interest rates, strong crypto returns from 2020, and perceived unique Web3 upside. Prominent VC participation encouraged institutions, showcasing classic venture network-validation effects.

Outcome: By the end of 2021, crypto VC merged firmly with mainstream VC. The year’s successes (OpenSea, Dapper, Solana, FTX at the time) underscored crypto’s enterprise value potential, while the resulting excesses paved the way for a necessary 2022 correction.

Bear Market Reset (2022–2023)

In 2022, the crypto venture party hit a wall. Macro headwinds and crypto-specific disasters triggered a sharp funding contraction and a return to conservative terms—a classic post-mania hangover.

Key factors defining the 2022–2023 reset:

Macro and Market Crash: Surging inflation and aggressive rate hikes battered risk assets. Bitcoin and Ethereum dropped around 75% from all-time highs, shrinking the crypto market from $3 trillion to under $1 trillion. Despite a strong Q1, crypto VC investment plunged roughly 68% in 2023 to about $10.7 billion, significantly below 2021 peaks.

Crypto-specific Catastrophes:

Terra/Luna collapse (May 2022): Erased over $40 billion in days, crippling several hedge funds and lenders.

FTX implosion (November 2022): A Lehman-scale shock forcing top VCs (Sequoia, Temasek, etc.) to write off hundreds of millions, shattering institutional trust.

Failures of Celsius, BlockFi, Genesis, and the Solana contagion further eroded confidence. SEC lawsuits against Ripple, Binance, and Coinbase added legal uncertainties.

These events sparked a “flight to quality”—investors prioritized clear-utility projects with solid teams and revenue, avoiding speculative or Ponzi-like ventures.

Valuation and Term Compression:

Median early-stage valuations dropped from over $30 million in 2021 to roughly $10–20 million by mid-2023. Down rounds and extensions became common, with unicorn valuations cut by 50–70%.

Investor-friendly terms returned: higher liquidation preferences, stronger anti-dilution protections, tighter governance, and board control.

LPs pushed for improved fund economics (lower fees, performance hurdles), making fundraising challenging for new crypto managers.

Survival of Players:

"Tourist" VCs exited; crypto-native investors doubled down, favoring seed/Series A deals with attractive valuations and longer horizons.

Ecosystem funds (e.g., Binance) stepped in to rescue or acquire promising but cash-starved projects.

Talent and developer activity consolidated around stronger chains and companies.

Regulatory Clarity vs. Crackdown:

The U.S. intensified enforcement while the EU implemented MiCA. Hong Kong, UAE, and Singapore rolled out crypto-friendly regulations.

U.S. deal share slightly declined as founders opted for friendlier jurisdictions and VCs hedged geographic risk.

Regulatory due diligence—token classification, exchange compliance, jurisdictional risk—became as critical as valuation.

Despite the gloom, mid-2023 saw green shoots: narratives around AI-crypto convergence, institutional ETF adoption, and real-world-asset tokenization hinted at fresh catalysts. Historically, downturn vintages often yield superior returns, prompting sophisticated LPs to urge selective yet active engagement.

The downturn purged weak structures: many 2021 SAFEs were repriced or converted, vesting schedules extended, and tokenomics re-engineered sustainably. Funds developed deep token-economics expertise, paralleling private-equity capital-structure rigor.

Present & Outlook (2024–2025)

As we step into 2024–Q2 2025, crypto venture capital finds itself on the rebound, albeit in a different form than 2021’s free-for-all. The industry has matured through adversity. Traditional and crypto-native venture practices are increasingly integrated, and investors are positioning for what they believe is the next up-cycle – whether that’s driven by new technology convergence, macro recovery, or simply the rhythm of innovation.

Following the market shake-out, crypto venture activity has shifted significantly towards the earliest stages. By 2024, about two-thirds of deals were Seed or Series A, with even many Series B/C rounds essentially supporting companies founded within the last 3–5 years. This early-stage focus arises from fewer late-stage survivors—many startups from 2017 either succeeded or exited—and a strategic emphasis on long-term bets poised to mature alongside market recovery. Galaxy Digital’s Q1 2025 research confirmed early-stage companies received most capital, highlighting robust deal flow at pre-seed and seed stages. For LPs, this signals capital deployment into long-horizon bets aligning with classic VC timelines, and smaller valuations could amplify returns if the sector revives (the vintage effect).

Realigned Sectors – RWAs, AI, and Beyond:

Real-World Assets (RWA) Tokenization: The tokenization of real-world assets (bonds, real estate, intellectual property) has gained substantial momentum, driven by improved blockchain scalability and clearer regulations. Funds are investing in startups developing infrastructure for RWAs, enabling on-chain trading of private equity or debt and incorporating real-world collateral into DeFi. These investments blend fintech with crypto, potentially unlocking large markets and generating quicker revenues than purely speculative crypto plays. Early indicators include banks piloting tokenized private credit and real estate, with some crypto funds already reporting paying users in RWA-focused portfolio companies.

Modular Blockchains and Layer-2 Scaling: Crypto’s technical roadmap emphasizes scaling via Layer-2 networks (L2s) and modular blockchain architectures, which separate execution, data availability, and consensus (e.g., rollups like Arbitrum and Optimism, or modular projects like Celestia and Fuel). VCs target these foundational technologies to solve blockchain limitations (speed, cost), supporting scalable apps like gaming and social networks. Many investments use SAFTs or token-equity combinations, anticipating significant token value accrual as these become essential infrastructure. By 2025, Ethereum’s upgrades and widespread L2 usage could significantly enhance user experience, potentially driving mass adoption and large returns—echoing historical VC bets on broadband or mobile infrastructure.

AI-Crypto Convergence: Generative AI’s emergence in 2023 sparked crypto investors’ interest in intersections such as blockchain-verified data, tokenized data-sharing, and decentralized AI computing or storage. Projects like Virtuals Protocol, Fetch.ai, Ocean Protocol, Bittensor, and SingularityNET drew renewed attention. Crypto funds allocated capital towards "AI meets Web3" startups, and some AI-focused funds explored crypto integrations. Autonomous AI agents operating in blockchain environments represent an exciting yet unproven synergy. LPs should scrutinize whether these ventures genuinely need blockchain or merely ride the hype. Nonetheless, leading funds like a16z actively cross-pollinate between crypto and AI sectors.

Structural Bets by Funds Now

Many crypto funds in 2024–2025 are adapting strategically to a shifting landscape:

Flexible Fund Lifecycles: Some funds extend durations (e.g., 12 years vs. traditional 10) or offer LP liquidity options, acknowledging tokens may mature slowly or face regulatory delays. LP give-back provisions and evergreen/open-ended fund structures, like Blockchain Capital’s shift, offer periodic liquidity, blending traditional venture with token flexibility.

Vertical Specialization & Expertise: Funds increasingly focus narrowly on specific sectors (DeFi, NFTs/gaming, infrastructure) and hire domain experts such as Solidity developers or gaming executives. Specialization reflects traditional VC evolution, helping LPs build diverse yet targeted portfolios.

Geographical Diversification: Funds manage jurisdictional risks by establishing international entities (Singapore, Dubai, Switzerland, Cayman). Regional crypto funds focusing on Latin America, Africa, or Southeast Asia attract local LPs, mirroring the rise of China or India-focused VC funds in earlier decades.

On-Chain DAOs & Tokenized Funds: On-chain investment DAOs (e.g., The LAO, BitDAO) and tokenized fund interests are innovative but limited in scale. These models enhance liquidity and participation, potentially evolving toward disciplined, transparent on-chain venture funding.

LP Priorities – Risk vs. Reward:

Downside Protection: Post-bear market, LPs prioritize risk management, asset custody, profit-taking strategies, and protocol risk evaluation.

Managed Liquidity: While liquidity is valued, LPs prefer GPs to strategically time exits, avoiding premature sales. Options like secondary markets and stablecoin distributions balance flexibility and protection.

Convexity (Upside Potential): Despite risks, crypto’s potential for outsized returns remains a major attraction. LPs seek skill-driven, repeatable outcomes, favoring clearly articulated scenarios (bull, base, bear) and diversified thematic portfolios.

Allocating Across the Crypto Spectrum:

CIOs now choose from:

Traditional VCs with occasional crypto exposure.

Hybrid firms (e.g., a16z, Paradigm) balancing crypto and equity investments.

Crypto-native venture funds with varied stages and strategies.

Liquid crypto vehicles (ETFs, hedge funds).

Institutional investors increasingly see crypto as essential within alternative asset strategies, typically allocating cautiously (initially 1–2%), balancing exposure and uncertainty.

Sources

https://blockworks.co/news/report-vcs-invested-33b-in-crypto-and-blockchain-startups-in-2021

https://www.galaxy.com/insights/research/crypto-venture-capital-q1-2025

https://historyofcomputercommunications.info/section/9.8/The-Return-of-Venture-Capital/

Risk Disclaimer:

insights4.vc and its newsletter provide research and information for educational purposes only and should not be taken as any form of professional advice. We do not advocate for any investment actions, including buying, selling, or holding digital assets.

The content reflects only the writer's views and not financial advice. Please conduct your own due diligence before engaging with cryptocurrencies, DeFi, NFTs, Web 3 or related technologies, as they carry high risks and values can fluctuate significantly.

Note: This research paper is not sponsored by any of the mentioned companies.